Sickles Seizes the Initiative, July 5, 1863

A Staff Officer Recalls the Tale of When Lincoln Visited Dan Sickles’ Sick Bed.

Words: Lt. Colonel James Rusling

From: “Lincoln and Sickles,” (1910)

It was Sunday, July 5, 1863, the Sunday after the Battle of Gettysburg. The battle, as you know, was fought heroically on both sides on July 1st, 2nd, and 3rd. In the terrible conflict of Thursday, July 2nd, held by many to have been the real battle of Gettysburg, because of the titanic fighting and awful Confederate losses, which took the life out of Lee's army. General Sickles, while in active command of the Third Corps, had been frightfully wounded by a Confederate ball or shell; his right leg had been amputated above the knee on the field; the next day or so, he was carried by his men, on a stretcher, to the nearest railroad (some miles away) and the Sunday following, arrived in Washington. He was taken to a private residence on F Street, nearly opposite to the Ebbitt House, where he had for several months reserved a floor for his own use. Here I found him on the first floor, reclining on a hospital stretcher, when I called to see him about 3 P.M. of that day. I was then Lieutenant Colonel and Chief Quartermaster on his staff, and naturally eager to see "My General". The only other officer present was Captain Fry, also of his staff, is now long since deceased. I found the General in much pain and distress at times, and weak and enfeebled from loss of blood, but calm and collected, and with the same iron will and clearness of intellect, that always characterized him in those Civil War days, and apparently always will. “He never dropped his cigar, nor lost the thread of his discourse, nor missed the point of their conversation.”

Naturally, we all three fell to talking about the battle, but had not been conversing long when General Sickles' orderly at the door announced "His Excellency the President", and immediately afterwards Mr. Lincoln strode into the room, accompanied by his little son "Tad", then a lad of ten or twelve years. He was staying out at the "Soldiers' Home" for the summer with his family. But having heard of General Sickles' arrival in Washington, he rode in on horseback, with a squad of cavalry as escort, to call upon him. He was tall and lanky; he wore a high silk hat ("stove pipe"), a long frock coat of black broad cloth, high top boots with trousers inside and spurs on; and altogether was about as ungainly a looking specimen of either statesman or cavalryman, as can well be imagined. The meeting between those two great men of that war period was cordial, though touching and pathetic, and it was easy to see they held one another in high esteem. They were both born American politicians, though of very different schools. They both loved the Union sincerely and heartily, and Sickles had already shown such high qualities, both as statesman and soldier, that Lincoln with his usual sagacity had been quick to perceive his value in the struggle then shaking the nation. Besides, Sickles was a prominent War Democrat, able and astute, and Lincoln was too shrewd to pass by any of these in those perilous war days, especially one who had raised a whole brigade of soldiers and placed them in the field, at his own expense, and commanded them ably and skillfully, as Sickles had done. This is a photograph taken by Matthew Brady in 1865, showing the southeast corner of F Street and 14th Street in Washington, D.C. This viewpoint is located opposite the home where General Sickles convalesced and met Abraham Lincoln on July 5, 1863.

Their first greetings over, Mr. Lincoln sat down and, crossing his prodigious arms and telescopic legs, soon fell to cross-examining General Sickles as to all the phases of the recent combat at Gettysburg. He inquired first, of course, as to Sickles' own ghastly wound, when and how it happened, and how he was getting on and encouraged him. Sickles was somewhat despondent, very naturally, but Lincoln "jollied" him, and said that he was something of a prophet that day, and that he would prophesy it would not be long before General Sickles would be out and up at the White House, where they would always be glad to see him. He passed next to our great casualties at Gettysburg, (equaling if not exceeding Wellington's at Waterloo) and how the wounded on both sides were being cared for; and finally came to the magnitude of our victory there and what Meade proposed to do with it. Sickles lay on his stretcher, with a cigar between his fingers, puffing it leisurely, and answered Mr. Lincoln in detail, but warily, as became so astute a man and so good a soldier; discussing the great battle and its probable consequences with a lucidity and ability remarkable for one in his condition — exhausted and enfeebled as he was by the shock of such a wound and amputation. Occasionally, he would wince with pain and call sharply to his valet to wet his fevered wound. But, when Mr. Lincoln's inquiries ceased, General Sickles, after a puff or two of his cigar in silence, renewed the conversation substantially. Dan Sickles (center), a regular attendee of Gettysburg reunions, is shown here at the twenty-fifth reunion in 1886.

“Well, Mr. President, pardon me, but what do you think about Gettysburg? What did you think about things, while we were campaigning up there?" "Oh" replied Mr. Lincoln, "I did not think much about them. I was not much concerned about Gettysburg." "Why, how was that?" rejoined Sickles excitedly, as if amazed. ''We heard you folks down here in Washington were much worried, and you certainly had good cause to be, for it was 'nip and tuck' with us much of the time!" "Yes, I know that. And I suppose we were a little 'rattled' now and then. Indeed, some of the Cabinet talked of Washington's being captured, and they ordered a gunboat here, and went so far as to send away some United States archives, and wanted me to go too, but I declined. Yes, Stanton and Welles, I believe, were both 'stampeded' somewhat, as we say out West, and Seward, I reckon, too. But, I said, 'No, gentlemen, I am not going aboard any gunboat; we are going to win at Gettysburg!' And we did, right handsomely. No, General Sickles, I had no fears of Gettysburg!" "Why, how was that, Mr. President? Why not? Everybody else down here, we heard, was more or less 'panicky'." "Yes, so I suspect, and a good many more than will own up to it now. But really. General Sickles, I had no fears of Gettysburg, and if you want to know why, I will try to tell you, confidentially. Of course, I don't want you to say anything about this now, nor Colonel Rusling here either. People might laugh, if it got out, you know. But the fact of the business is, in the pinch of the campaign up there, when we had sent General Meade all the soldiers we could rake and scrape, and yet everything seemed going wrong, Washington endangered, Baltimore threatened, Philadelphia menaced, and the whole country in an uproar, I went into my room one morning and locked the door, and got down on my knees, and prayed Almighty God for victory at Gettysburg. I confess I was at my very wit's end. I told the Almighty this was his country, and our war His war, but we could not stand anotherFredericksburg, or Chancellorsville, or Peninsula campaign. And then and there I made a solemn vow with my Maker, that if He would stand by you boys at Gettysburg, I would stand by Him! I prayed, 'Oh God, have mercy upon me and my afflicted people ! Our burdens and sorrows are greater than we can bear! Come now and help us, or we must all likewise perish! And Thou canst not afford to have us perish! We are Thy chosen people, the last best hope of the human race !' And so I 'wrestled' with Him, as Abraham or Moses in ancient days. And after so 'wrestling' with God, sincerely and devoutly, in solemn prayer, for a considerable time, I don't know how it was and I can't explain it (I'm not a 'Meeting man', you know), but somehow or other a sweet comfort crept into my soul, that God Almighty had taken the whole business up there into His own hands, and things would come out all right at Gettysburg. And He did stand by you boys there, and now I will stand by Him! No, General Sickles, I had no fears of Gettysburg, and that is why!" Mr. Lincoln said all this with great solemnity. When he had concluded, there was a silence, that nobody seemed disposed to break. Mr. Lincoln especially appeared to be communing with the Infinite One again, with a strange look of introspection upon his face, while General Sickles continued to puff his cigar, but more slowly. The first to speak was General Sickles, who presently resumed as follows: "Well, Mr. President, what do you think about Vicksburg, nowadays? How are things getting along down there?" "0h", answered Lincoln, very gravely. "I don't quite know. Grant is in command down there, and still keeps 'pegging away' at the enemy. And I rather think, as we used to say out in Illinois, he 'will make a spoon or spoil a horn' before he gets through. Some of our Senators and Congressmen think him slow, and want me to remove him. But, to be honest, I kind of like U. S. Grant. He doesn't worry and bother me. He isn't shrieking for reinforcements all the time, like some of our other Generals. He takes what soldiers we can give him, considering our big job all around, and we have a big job in this war, and does the best he can with what he has got, and does not grumble and scold all the while at me and Stanton like some others. Yes, I confess, I like General Grant, U. S. Grant, United States Grant, Uncle Sam Grant, Unconditional Surrender Grant. There is a great deal to him, first and last. And Heaven helping me, unless something happens more than I know now, I mean to stand by Grant a good while yet. He fights; he fights!" “Sickles lay on his stretcher, with a cigar between his fingers, puffing it leisurely, and answered Mr. Lincoln in detail.”

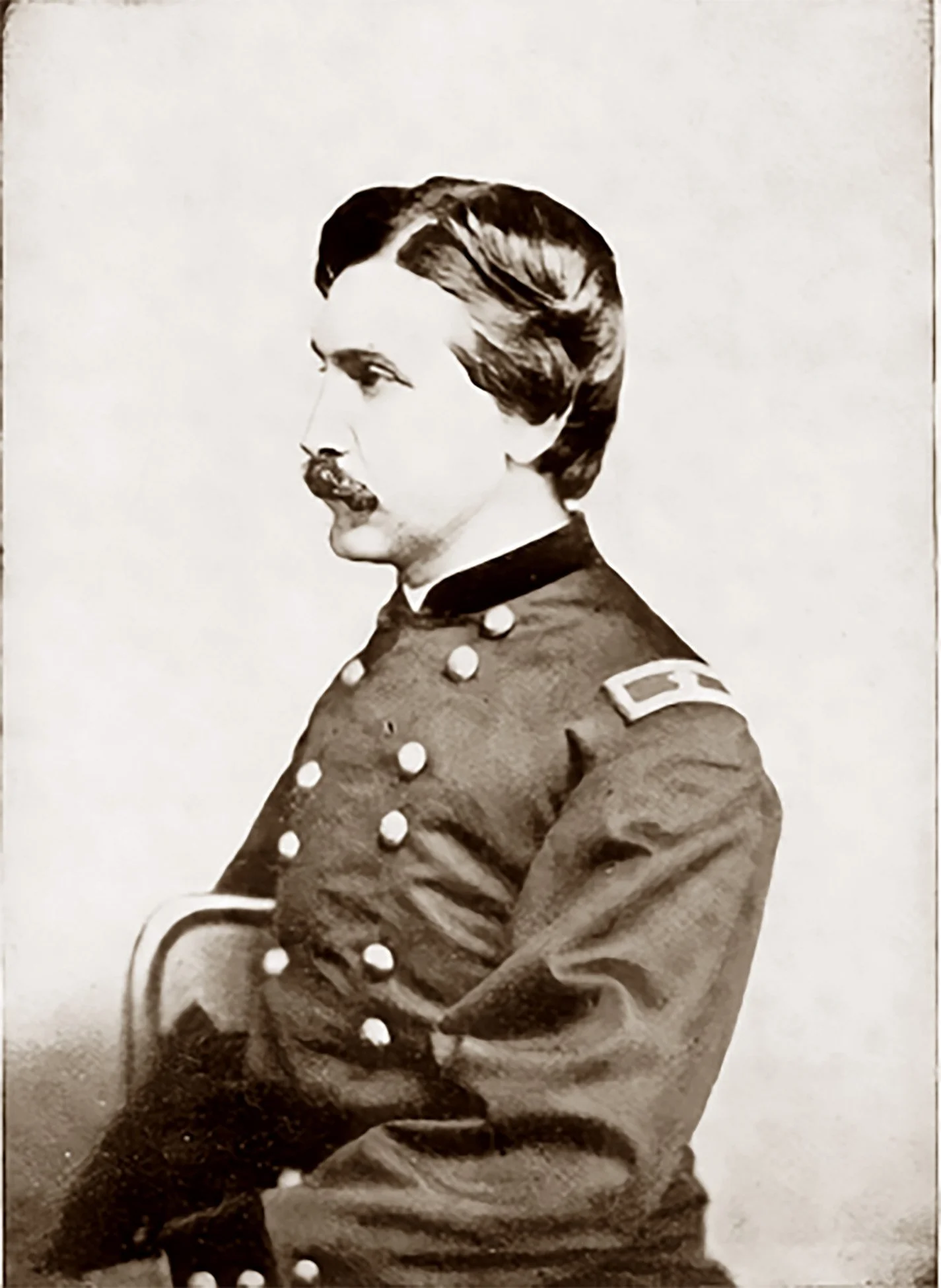

"So then, you have no fears to-day about gentlemen, I am not going aboard any gunboat; we are going to win at Gettysburg!' And we did, right handsomely. No, General Sickles, I had no fears of Gettysburg!" "Why, how was that, Mr. President? Why not? Everybody else down here, we heard, was more or less 'panicky'." "Yes, so I suspect, and a good many more than will own up to it now. But really. General Sickles, I had no fears of Gettysburg, and if you want to know why, I will try to tell you, confidentially. Of course, I don't want you to say anything about this now, nor Colonel Rusling here either. People might laugh, if it got out, you know. But the fact of the business is, in the pinch of the campaign up there, when we had sent General Meade all the soldiers we could rake and scrape, and yet everything seemed going wrong, Washington endangered, Baltimore threatened, Philadelphia menaced, and the whole country in an uproar, I went into my room one morning and locked the door, and got down on my knees, and prayed Almighty God for victory at Gettysburg. I confess I was at my very wit's end. I told the Almighty this was his country, and our war His war, but we could not stand anotherFredericksburg, or Chancellorsville, or Peninsula campaign. And then and there I made a solemn vow with my Maker, that if He would stand by you boys at Gettysburg, I would stand by Him! I prayed, 'Oh God, have mercy upon me and my afflicted people ! Our burdens and sorrows are greater than we can bear! Come now and help us, or we must all likewise perish! And Thou canst not afford to have us perish! We are Thy chosen people, the last best hope of the human race !' And so I 'wrestled' with Him, as Abraham or Moses in ancient days. And after so 'wrestling' with God, sincerely and devoutly, in solemn prayer, for a considerable time, I don't know how it was and I can't explain it (I'm not a 'Meeting man', you know), but somehow or other a sweet comfort crept into my soul, that God Almighty had taken the whole business up there into His own hands, and things would Vicksburg either, Mr. President", added General Sickles. General James Fowler Rusling, a confidant and officer of General Sickles' staff, wrote the only known account of the meeting of Dan Sickles and Abraham Lincoln, July 5, 1863. (Dickenson College Archives)

Well, no, I can't say I have," replied Mr. Lincoln, very soberly but firmly, "the fact is — but don't say anything about this either just now — I have been praying over Vicksburg also. I have 'wrestled' with Almighty God, and told him how much we need the Mississippi, and how it ought to flow 'unvexed to the sea/ and how its great valley ought to be forever free, and I reckon He understands the whole business down there, 'from A. to Izzard'. I have done the very best I could to help Grant, and all the rest of our generals (though some of them don't think so) ; and now it is kind of borne in on me, that somehow or other we are going to win at Vicksburg too. I cannot tell how soon. But I believe we will. For this will save the Mississippi and bisect the Confederacy, and be in line with God's everlasting laws of righteousness and justice. And if Grant only does this thing down there — I don't care much how, so he does it right — why Grant is my man and I am his the rest of this war!" General Sickles, recovered from the loss of his leg, is seated in the center surrounded by his staff of four officers. (Library of Congress)

Of course, President Lincoln did not at that moment know that Vicksburg had already fallen on July 4th, and that a United States gunboat was then speeding its way up the Mississippi to Cairo with the glorious news, that was soon to thrill America and the civilized world through and through. Gettysburg and Vicksburg! Our great twin victories of the Civil War ! What were they not to the Union in that fateful summer of 1863? And what would have happened to the American Republic had both gone the other way? Of course, I do not pretend to say, that Abraham Lincoln's faith and prayers saved Gettysburg and Vicksburg. But they certainly did not do the Union any harm. And the serene confidence of the beleaguered President, was an unspeakable comfort and joy on that memorable July 5, 1863. James Rusling frequently discussed his fateful meeting with Lincoln and Sickles, often elaborating on the event. Fifty years later, he was still recalling the event and added the following passage, suggesting that the Sickles meeting was more eventful than it was.

“He (Sickles) certainly got his side of the story to Gettysubrg well into the President’s mind and heart that Saturday afternnon; and this doubtless stood him in good stead afterwar, when Meade proposed to court-martial him for fighting so magnificantly, if unskillfully (which remains to be proven), on that bloody and historic July 2nd.” - Lt. Colonel James Rusling

I never saw President Lincoln again. But this conversation made a deep and lasting impression upon me. I have told it hundreds of times since, both publicly and privately. It has passed into American and English histories, and gone around the world. Clearly it fixes the quaestio vexata of Abraham Lincoln's Religious Faith, unless he was a hypocrite and humbug, which is unthinkable. Perhaps I should add, I wrote home about it the same day, and now give it here as the very truth of history, much of it ipsissim averha. General Sickles himself, has also corroborated it substantially, on many occasions, both publicly and privately. I count it one of the chief honors of my life, that I was present and privileged to hear it. Would you be interested in reading more on the Sickles-Meade controversy? The best places to start are James Hessler's Sickles at Gettysburg (Savas Beatie, 2009) and Richard A. Sauers' Gettysburg: The Meade-Sickles Controversy (Potomac Books, 2003).