“Now He Belongs to the Ages”

Edwin Stanton (above), the Secretary of War known for his acidic tongue and stoic disposition, had a moment of eloquence at the president's passing.

Few incidents in the annals of American history can match the tragedy that befell the nation on the evening of April 14, 1865. President Abraham Lincoln, in a celebratory mood following the surrender of Lee's forces at Appomattox, was struck down at Ford's Theatre by the hand of the assassin John Wilkes Booth. Just three nights before, the president gave a speech from the North Portico of the White House stressing reconciliation with the South, and now he lay dying at a boarding house across the street from the theatre. Many contemporary accounts and later historians document exhaustively the hour-by-hour details of the plot to overthrow the government by assassinating the head of state and cabinet officials. Still, one quote seems to encapsulate the moment and has become part of the mythology around the demise of the sixteenth president and his memory. The quote comes from the unlikeliest of men: Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War known for his acidic tongue and stoic disposition, had a moment of eloquence when, at the president's passing, he proclaimed, "Now, he belongs to the ages." The last know photograph of Abraham Lincoln taken February 5, 1865

The quote is familiar to many; it appears in hundreds of accounts of Lincoln's life, but the source of the quote is more arcane. At precisely 10:13 p.m., Booth entered the presidential box at Ford's Theatre and fired a single shot in the back of the president's head with a Derringer pistol. Just barely alive but with a mortal prognosis, the notion of dying on Good Friday in a playhouse loomed; the president was taken across the street to a William Peterson boarding house to die with dignity in a proper bed. Robert Todd Lincoln, the president's eldest son, and his friend John Hay, Lincoln's personal secretary and the quote's source, were in the Executive Mansion gossiping about events when a crowd of people burst into the White House with a wild tale of murder and conspiracy. At the same time, Edwin Stanton, prepared for bed when a ring of the doorbell brought ill news; the mob in the streets, growing by the thousands, confirmed the rumor that the president had been mortally wounded. Stanton went to the boarding house to take control of the situation. When entering the boarding house, Stanton decided to remain by the president. The Peterson boarding house became a makeshift War Department where the secretary of war managed the pursuit of the assassins and kept vigil over the fading a president. One of two drawings by Hermann Faber made at Lincoln's death bed.

Death came to President Lincoln at 7:22 a.m. The attending doctors and everyone confirmed the time with their timepieces. "He is gone," one of the doctors said. It was a crowded scene, according to the observant John Hay who counted twenty people including himself, in the room. From the hand of John Hay comes the end of the sixteenth president: "His automatic moaning, which had continued through the night, ceased; a look of unspeakable peace came upon his worn features. At twenty-two minutes after seven, he died. Stanton broke the silence by saying, 'Now he belongs to the ages.'"

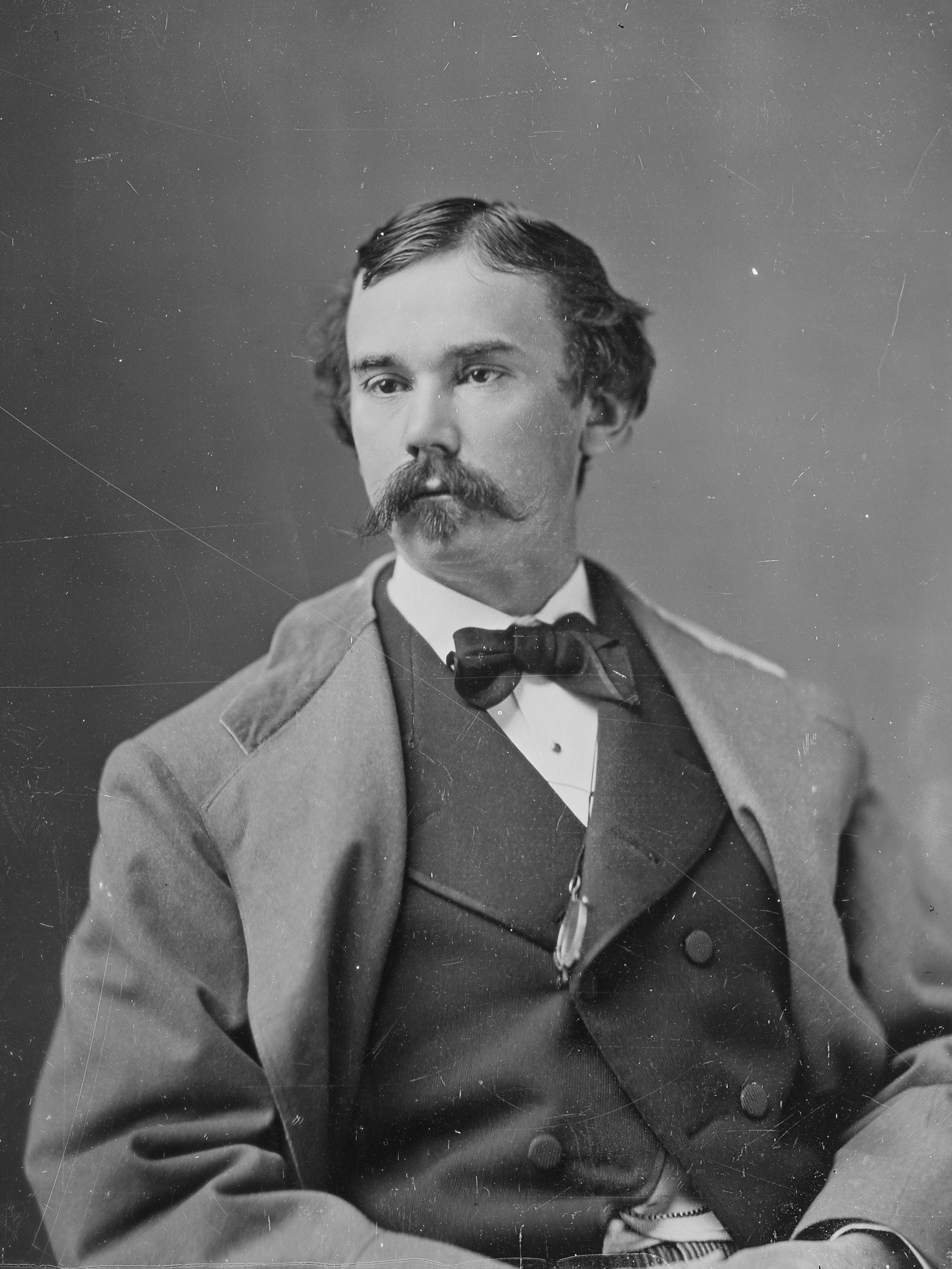

John Hay

The man known for browbeating army contractors and subordinates, who earlier that evening, having heard enough of Mary Todd Lincoln's weeping aloud, demanded "Take that woman out and do not let her in again," had somehow found the inner peace to sum up the evening's events in a national soliloquy.

Edwin Stanton never had the opportunity to recognize the reputation of his deathbed statement; he outlived the president by only four years, dying in agony from the throes of an asthma attack on Christmas Eve 1869. It was not until 1890, John Hay and John Nicolay, the two private secretaries of President Lincoln, published the magisterial ten-volume work entitled Abraham Lincoln: A History where the quote was first described. Most of the work is based on Lincoln's personal papers and some based on the memory of the two secretaries. Serial installments of the work began to appear in the Century Magazine in January 1890, the excerpt of the assassination of the president was included with the Stanton quote. By the first week of January 1890, many newspapers picked up the quote.

As with all things involving the Civil War, nothing is a final, definitive word. Some accounts suggest that Stanton said Lincoln "belongs to the angels now," but the standard version seems the most prevalent in Lincoln historiography.

The Lincoln biography popularized the quote from Stanton and elevated young John Hay in popularity. He enjoyed a lifetime of public service as Ambassador to the United Kingdom under the McKinley Administration and Secretary of State under Teddy Roosevelt. He died in 1905.All images are from the Library of Congress